Stockmarkets

The bear necessities

Stockmarket woes worsen

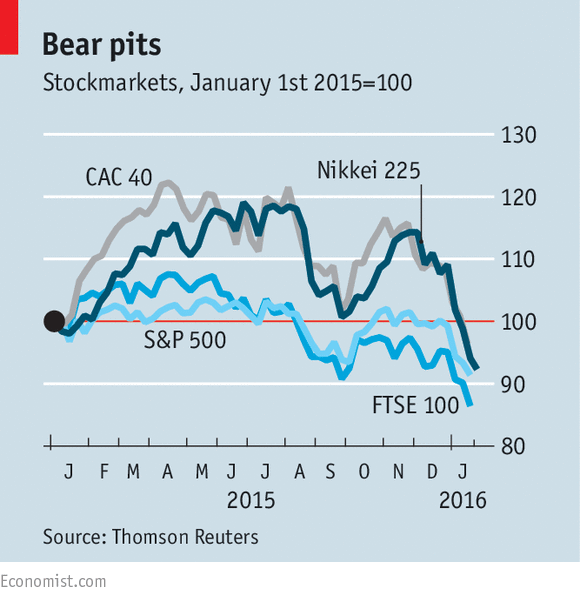

BEAR markets are triggered, by convention, when share prices fall by more than 20%. So the widespread stockmarket declines on January 20th took Tokyo’s Nikkei 225, London’s FTSE 100 and France’s CAC-40 into bear-market territory (see chart), since all had declined at least that much since their highs of last year. Mind you, another old saw is that bear markets do not end until prices pass their previous peak; on that measure, the Nikkei 225, which is less than half its 1989 high, is still caught in a 26-year-long bear run.

The rich world is not alone in its ursine infestation. China’s CSI 300 index is more than 40% below last year’s high. The FTSE All-World Index, having breached the 20% mark, ended down 19% on January 20th. Indeed New York, although hit hard that day (the Dow Jones Industrial Average fell more than 500 points at one stage, before rebounding a bit), is one of the few big markets not to have entered bearish territory.

Among the primary causes of the sell-off is worry about China’s economic health, despite the latest GDP numbers, published this week, that were in line with forecasts of 6.9% growth.

Investors fear that the real numbers are worse than the official data suggest, and see the sharp fall in commodity prices, particularly oil, as evidence for the hypothesis of weaker Chinese demand.

In a sense, equity markets are only catching up with the bearish implications of moves in other markets, such as the rise last year in corporate-bond spreads (the interest-rate premiums paid by riskier borrowers). Higher spreads usually reflect fears that more borrowers will default in the face of adverse economic conditions. Investors have also been rushing for the perceived safety of government bonds, with the yield on ten-year American Treasuries falling back below 2%. In June it was nearly 2.5%.

Forecasts for global growth this year are being revised down, as they have been for the past few years. The IMF has cut its estimate from 3.6% to 3.4%. World trade has also been worryingly sluggish, with volumes falling in the first half of 2015.

So far manufacturing appears to have been hit harder than services, with industrial production in America falling in each of the last three months of 2015. But a wide range of companies are facing a squeeze in profits. Macy’s, a retailer, IBM, a computer-services company, and Shell, an oil giant, all recorded big declines in their latest results. Overall, the profits of the constituent companies of the S&P 500 index in the fourth quarter of 2015 are expected to be down by almost 5% on the same period a year earlier.

Part of the sell-off in global equities may reflect this reduced outlook for profits. In a recent survey of fund managers by Bank of America-Merrill Lynch, more than half expected profits to decline further over the next 12 months. Cash now makes up 5.4% of portfolios, the third-highest level since 2009. But fund managers are not as bearish as they might be: a net 21% of them have a bigger weighting in equities than usual and only 12% expect a global recession in the next year.

Some also blame the Federal Reserve for pushing up interest rates in December. To the extent that monetary policy, via both low rates and quantitative easing, has pushed up asset prices since 2009, the fear is that tighter policy may drag those prices back down. But the stockmarket decline may be altering the outlook for monetary policy, too.

Back in September, when the markets were suffering another tumble, the Fed stepped back from a rate rise, citing fears about a slowing global economy. Judging by the futures market, investors think the Fed will take fright again: they are now expecting it to raise rates only once this year, when previously they had been expecting three increases.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario