The Rise Of Long-Term Thinking

Jan. 5, 2014 3:40 AM ET

.

Morgan Housel has penned a rather odd column to mark the new year, declaring 2013 to be the year that "long-term thinking" died, with "his last true friend, Vanguard founder Jack Bogle," at his side.

The weird thing about this column is that long-term thinking isn't dead at all; in fact, it's never been healthier. Housel did manage to find a trader on CNBC exhibiting symptoms of short-term thinking - but that's what CNBC does, and in fact it's possible to use CNBC's ratings as a reasonably good proxy for the general prevalence of short-term thinking.

Guess what: they're at their lowest point in 20 years, with the channel reaching just 38,000 viewers over the course of a day. That's a really tiny niche. A potentially profitable niche, to be sure, but tiny all the same.

Meanwhile, long-term thinking's true friends at Vanguard have never been healthier: the Vanguard Total Stock Market Index Fund is now the largest mutual fund in the world, having overtaken the Pimco Total Return Fund in October, and Vanguard's total assets under management are jaw-droppingly huge: they started last year at $2 trillion, and were already over $2.5 trillion by the end of June. I wouldn't be surprised if they were at or near $3 trillion by now. It's pretty safe to say that substantially all of that money is being invested according to the tenets of long-term thinking - and that it vastly exceeds the amount of money being traded on a daily basis by the 38,000 viewers of CNBC. (They'd need to have $80 million each to get to $3 trillion; and while CNBC viewers might be rich, they're not that rich.)

The height of short-term thinking, when it comes to investing, was surely the dot-com bubble, when everybody wanted to be a day trader, and everybody believed in the greater fool theory. When the dot-com bubble burst, individuals (outside a core group of hobbyists) pretty much gave up on stock-picking and short-term trading. With hindsight, we can even say that the dot-com burst was very well timed to prepare America's investors for the financial crisis: once they had lived through 1999-2001, they grew up, and ended up responding to the crisis in a surprisingly mature and sensible manner.

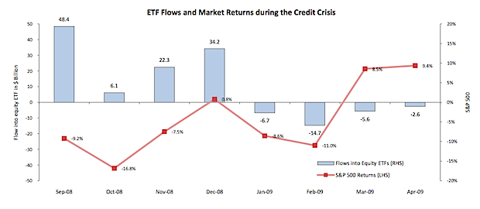

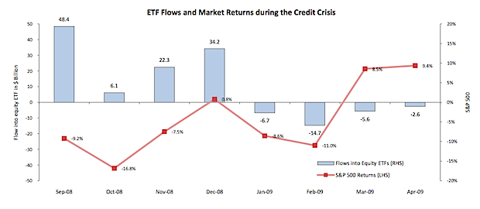

Here, for instance, is a chart of ETF flows during the crisis:

(click to enlarge)

What you're looking at here are some of the most torrid months that stock-market investors have ever seen. Just look at the monthly return figures on the S&P 500, from September 2008 through February 2009: -9.2%, -16.8%, -7.5%, +0.8%, -8.6%, -11.0%. Add it all up, and you get a stomach-churning 42% drop in the market - more than enough, according to conventional wisdom, to spark a major panic among retail investors. But what did they actually do? They ended up putting a net new $90 billion into ETFs over the course of those months.

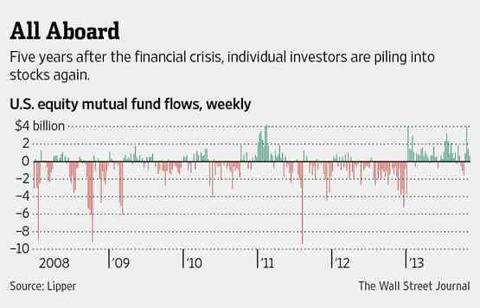

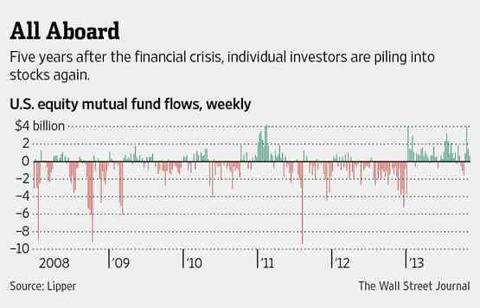

Or, here's a chart of mutual fund flows - a chart which naturally exaggerates outflows, since there's a long-term secular trend out of mutual funds and into ETFs. Again, there's no real sign of panic during the financial crisis: there was selling, to be sure, at a time when Americans found themselves in sudden need of liquidity, but you're not seeing any short-term thinking here: you're not seeing people trying to time the market. More generally, the main lesson of this chart is how small all the numbers are.

Compared to the trillions invested in the stock market, weekly flows in the single-digit billions are pretty small beer, and show that nearly all investors, nearly all of the time, are doing the sensible buy-and-hold thing. When flows are small relative to stocks, that bespeaks long-term thinking, rather than short-term thinking.

(click to enlarge)

This is not the impression that you get from talking to professional financial advisers, of course, most of whom paint themselves as a desperately-needed bulwark protecting investors from their base instincts. And it's not the impression that you get from reading scaremongering stories about high-frequency trading, or misleading statistics from the likes of Housel, who says that the average stock holding period fell from eight years to five days between the 1960s and 2010. The problem with such numbers is that averages are little use to us here: a very small number of high-frequency algobots, who can hold their positions for less than a second, will skew the averages to the point of meaninglessness.

Indeed, a big reason for the rise and rise of private markets, and the ever-increasing amount of time that companies wait before they go public, is precisely that there is an unprecedentedly large pool of long-term patient money out there, willing to tie itself up in private-equity and venture-capital funds for five or ten years or longer. Individuals are looking for investment advice not so much from the braying noisemakers on CNBC, but rather from institutions with quasi-permanent capital pools: endowments, foundations, sovereign wealth funds.

Or, to put it another way, the war has pretty much been won at this point, and retail investors have got the message. They understand the superiority of passive investing, and they understand the importance of long-term thinking: none of these things, any more, are remotely difficult or counterintuitive concepts.

Housel's column is in effect an attempt to persuade the sensible majority that they're some kind of beleaguered minority. In reality, however, long-term thinking is alive and well and utterly mainstream. Which should good news for everybody, with the possible exception of CNBC.

The weird thing about this column is that long-term thinking isn't dead at all; in fact, it's never been healthier. Housel did manage to find a trader on CNBC exhibiting symptoms of short-term thinking - but that's what CNBC does, and in fact it's possible to use CNBC's ratings as a reasonably good proxy for the general prevalence of short-term thinking.

Guess what: they're at their lowest point in 20 years, with the channel reaching just 38,000 viewers over the course of a day. That's a really tiny niche. A potentially profitable niche, to be sure, but tiny all the same.

Meanwhile, long-term thinking's true friends at Vanguard have never been healthier: the Vanguard Total Stock Market Index Fund is now the largest mutual fund in the world, having overtaken the Pimco Total Return Fund in October, and Vanguard's total assets under management are jaw-droppingly huge: they started last year at $2 trillion, and were already over $2.5 trillion by the end of June. I wouldn't be surprised if they were at or near $3 trillion by now. It's pretty safe to say that substantially all of that money is being invested according to the tenets of long-term thinking - and that it vastly exceeds the amount of money being traded on a daily basis by the 38,000 viewers of CNBC. (They'd need to have $80 million each to get to $3 trillion; and while CNBC viewers might be rich, they're not that rich.)

The height of short-term thinking, when it comes to investing, was surely the dot-com bubble, when everybody wanted to be a day trader, and everybody believed in the greater fool theory. When the dot-com bubble burst, individuals (outside a core group of hobbyists) pretty much gave up on stock-picking and short-term trading. With hindsight, we can even say that the dot-com burst was very well timed to prepare America's investors for the financial crisis: once they had lived through 1999-2001, they grew up, and ended up responding to the crisis in a surprisingly mature and sensible manner.

Here, for instance, is a chart of ETF flows during the crisis:

(click to enlarge)

What you're looking at here are some of the most torrid months that stock-market investors have ever seen. Just look at the monthly return figures on the S&P 500, from September 2008 through February 2009: -9.2%, -16.8%, -7.5%, +0.8%, -8.6%, -11.0%. Add it all up, and you get a stomach-churning 42% drop in the market - more than enough, according to conventional wisdom, to spark a major panic among retail investors. But what did they actually do? They ended up putting a net new $90 billion into ETFs over the course of those months.

Or, here's a chart of mutual fund flows - a chart which naturally exaggerates outflows, since there's a long-term secular trend out of mutual funds and into ETFs. Again, there's no real sign of panic during the financial crisis: there was selling, to be sure, at a time when Americans found themselves in sudden need of liquidity, but you're not seeing any short-term thinking here: you're not seeing people trying to time the market. More generally, the main lesson of this chart is how small all the numbers are.

Compared to the trillions invested in the stock market, weekly flows in the single-digit billions are pretty small beer, and show that nearly all investors, nearly all of the time, are doing the sensible buy-and-hold thing. When flows are small relative to stocks, that bespeaks long-term thinking, rather than short-term thinking.

(click to enlarge)

This is not the impression that you get from talking to professional financial advisers, of course, most of whom paint themselves as a desperately-needed bulwark protecting investors from their base instincts. And it's not the impression that you get from reading scaremongering stories about high-frequency trading, or misleading statistics from the likes of Housel, who says that the average stock holding period fell from eight years to five days between the 1960s and 2010. The problem with such numbers is that averages are little use to us here: a very small number of high-frequency algobots, who can hold their positions for less than a second, will skew the averages to the point of meaninglessness.

Indeed, a big reason for the rise and rise of private markets, and the ever-increasing amount of time that companies wait before they go public, is precisely that there is an unprecedentedly large pool of long-term patient money out there, willing to tie itself up in private-equity and venture-capital funds for five or ten years or longer. Individuals are looking for investment advice not so much from the braying noisemakers on CNBC, but rather from institutions with quasi-permanent capital pools: endowments, foundations, sovereign wealth funds.

Or, to put it another way, the war has pretty much been won at this point, and retail investors have got the message. They understand the superiority of passive investing, and they understand the importance of long-term thinking: none of these things, any more, are remotely difficult or counterintuitive concepts.

Housel's column is in effect an attempt to persuade the sensible majority that they're some kind of beleaguered minority. In reality, however, long-term thinking is alive and well and utterly mainstream. Which should good news for everybody, with the possible exception of CNBC.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario