The Nobel Laureates on equity bubbles

By Gavyn Davies

October 20, 2013 2:41 pm

It is also of relevance to the likely next Chair of the Fed, Janet Yellen, who will be closely examined about bubbles in her confirmation process. In the past, she has strongly argued that the Fed should not use standard monetary policy to deal with bubbles [1].

Many people have commented that two of the Nobel Laureates, Eugene Fama and Robert Shiller have polar opposite views about the theoretical possibility of bubbles [2]. Fed Governor Jeremy Stein said on Friday that this debate is “paradigm-versus-paradigm stuff”. One is right, the other is wrong, and the Fed needs to know which is which.

Professor Fama, the founder of efficient market theory, has said that he does not really understand what bubbles are, or how bubbles can exist, even after the implosion of the housing and credit markets in 2005-08 [3]. He is probably being deliberately provocative about this, but it is important to understand what he means.

Fama acknowledges that economists have a widely-accepted definition of a “bubble”, which is that the asset price has deviated sharply from the level justified by fundamentals. For the equity market, the price justified by fundamentals is given by the expected future flow of dividend payments, discounted by the required future return on the asset. The required return is equal to the risk free rate, plus the equity risk premium. Obviously, an increase in the expected flow of dividends raises the equity price, while a rise in the required rate of return reduces it.

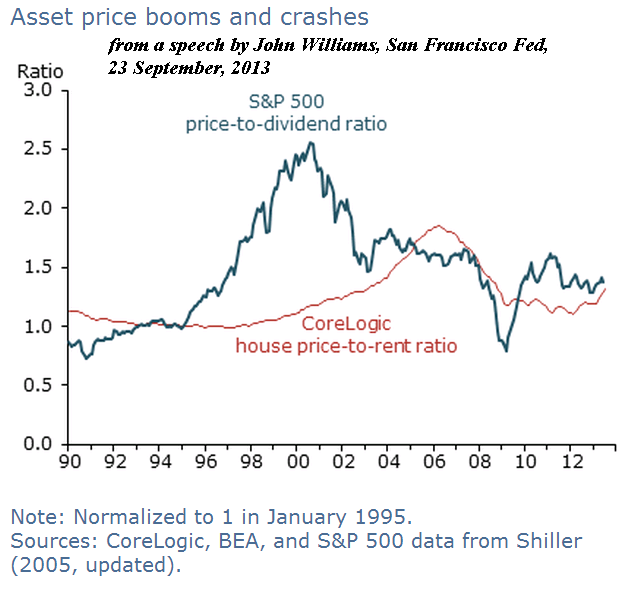

We know from the work of Robert Shiller that asset prices, notably equity and house prices, are far more volatile than can be explained by variations in the future flow of dividends and rents, or in the risk free rate. This is also accepted by the Chicago School, as explainedhere by John Cochrane, Fama’s son-in-law and also his intellectual heir. This means, by process of elimination, that the large variations in asset prices, which might be called bubbles, stem from changes in the equity risk premium, or in a residual factor which is not identified. This is where the difference between Fama and Shiller arises.

We know from the work of Robert Shiller that asset prices, notably equity and house prices, are far more volatile than can be explained by variations in the future flow of dividends and rents, or in the risk free rate. This is also accepted by the Chicago School, as explainedhere by John Cochrane, Fama’s son-in-law and also his intellectual heir. This means, by process of elimination, that the large variations in asset prices, which might be called bubbles, stem from changes in the equity risk premium, or in a residual factor which is not identified. This is where the difference between Fama and Shiller arises.

Fama basically thinks that most of the variation in asset prices (almost by definition in his world) is determined by changes in risk appetite. When risk appetite is high, the future return required is low, so the equity risk premium is low. This means that the discount rate applied to future dividends will be low, and the equity market will be at a high level [4].

In Fama’s approach, the market almost always remains at equilibrium, given the risk appetite prevailing at any given time, even though the market level fluctuates much more than fundamentals like dividends would suggest. There is no irrationality involved in this, no opportunity to “beat the market” (except by accepting a different level of risk from the market as a whole), and therefore no case for the Fed to intervene to smooth a “bubble”.

Shiller’s approach is very different. He believes that it is implausible that the risk appetite in the financial markets changes in a manner which can explain the over-reaction of equities (and house prices) to the relevant economic fundamentals. (In fact, he was the first person to establish that prices behave like this, and the first to point out that this is a major problem for efficient markets.) In the absence of a plausible explanation based on risk appetite, he suggests that the explanation must lie in behavioural factors, including the possibility of irrational bubbles in the asset price.

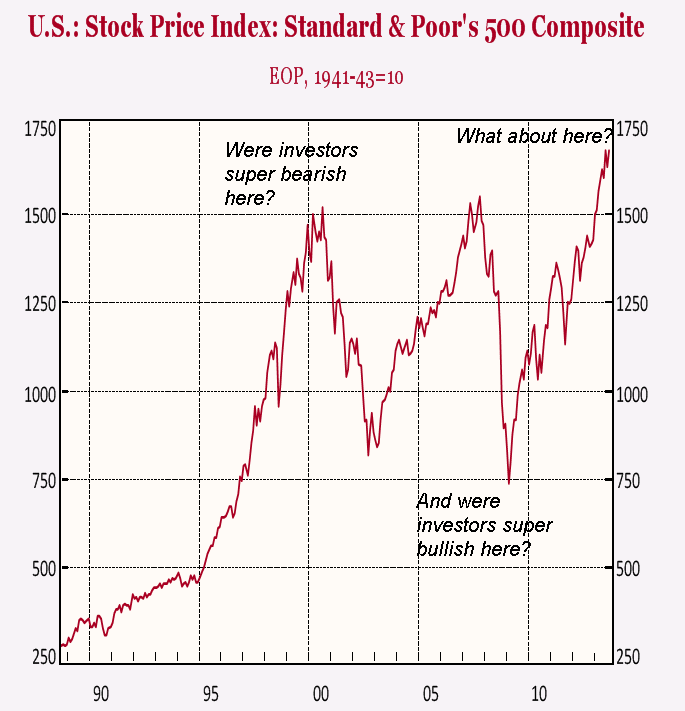

John Cochrane says that empirical work has so far failed to determine conclusively whether Fama or Shiller is right. However, recent work has, in my opinion, been supportive of Shiller’s interpretation. It is certainly a strong positive that the medium term predictions for asset prices derived from his model have been successful (see Brad DeLong here). But the decisive factor is what actual investors say about their expectations of future returns at different points of the cycle in asset prices. Recall that, in the Fama explanation, investors are supposed to be pessimistic about future returns when prices are high, and optimistic when prices are low. Shiller, in contrast, expects investors to be bullish at the top of the market, and vice versa.

John Cochrane says that empirical work has so far failed to determine conclusively whether Fama or Shiller is right. However, recent work has, in my opinion, been supportive of Shiller’s interpretation. It is certainly a strong positive that the medium term predictions for asset prices derived from his model have been successful (see Brad DeLong here). But the decisive factor is what actual investors say about their expectations of future returns at different points of the cycle in asset prices. Recall that, in the Fama explanation, investors are supposed to be pessimistic about future returns when prices are high, and optimistic when prices are low. Shiller, in contrast, expects investors to be bullish at the top of the market, and vice versa.

Most practising investors would have little doubt, based on experience, that Shiller’s view on this sounds a lot more plausible than Fama’s: when markets are near their peaks, investor opinion is often at its most bullish, because people tend to extrapolate the recent rise in prices into the future. At the bottom of the market, by contrast, gloom is all-pervasive.

And this is exactly what has been found in recent empirical work, notably by Robin Greenwood and Andrei Shleifer at Harvard. They show that a collection of different surveys of investor opinion strongly suggest that markets do indeed extrapolate the recent direction of asset prices when they form their expectations, which implies that they expect the highest future returns when prices are near their cyclical peaks.

In Fama’s world, this represents inefficient bubble-like behaviour, which should be eliminated by an influx of rational investors taking the opposite point of view. But in practice this does not seem to happen. Instead, investors behave in herd like fashion in the short term, driving asset prices higher and higher [5]. Only in the medium or long term do these anomalies correct themselves.

In Jeremy Stein’s battle of the paradigms, it therefore seems that the Fed should be paying more attention to the warnings of Shiller than to the reassurance of Fama. Bubbles can happen, but of course that does not automatically mean that we are in one now. Shiller’s market valuation measures for equities and housing are not yet abnormally high, and new econometric techniques for detecting bubbles (recent results from which will be outlined in a forthcoming blog) are mostly reassuring.

So the Fed should certainly be on the look-out for bubbles, but not necessarily taking action yet.

———————————————————————————————–

Footnotes

[1] In 2005, Ms Yellen, in an unfortunate quote, said:

First, if the bubble were to deflate on its own, would the effect on the economy be exceedingly large? Second, is it unlikely that the Fed could mitigate the consequences? Third, is monetary policy the best tool to use to deflate a house-price bubble? My answers to these questions in the shortest possible form are, “no,” “no,” and “no.”

At the time, the San Francisco Fed was in the forefront of Fed research arguing that the control of bubbles should not be a matter for standard monetary policy. This has changed, as this excellent speech by San Francisco Fed Chairman John Williams demonstrates. (It also develops many of the points in this blog in greater depth.) It remains to be seen whether Ms Yellen has joined her former colleagues in changing her approach on this.

[2] The work of the third winner, Lars Peter Hansen, is summarised by John Cochrane here. For a more straightforward piece on the contribution of all three winners, see this accessible essay by Daniel Davies at Crooked Timber. See also Paul Krugman on why the prizes were merited, Tim Harford on why the efficient market theory merited the Nobel, Mark Thoma on why efficient markets theory is useful, and Mark’s compendium of other web entries on the Nobel this week.

[3] Fama, in reply to a question from John Cassidy, said: “I don’t know what a credit bubble means. I don’t even know what a bubble means. These words have become popular. I don’t think they have any meaning.”

[4] John Williams neatly explains this as follows: “If rational investors discount future dividends by less, perhaps owing to a reduction in risk aversion, then the price-to-dividend ratio rises and we see a boom in the asset price. And the expected future rate of return on the now higher-priced asset will be correspondingly lower.”

[5] This does not mean that it is easy to make money in the short term by betting against the crowd, because it is hard to time the top and bottom of bubbles accurately. The weak or semi-strong form of Fama’s efficient market hypothesis (EMH), states that public information is fully reflected in asset prices. It can be true that it is difficult to beat markets in the short term, without believing that market prices are always economically optimal. Active investors attempt to find anomalies and exceptions to the EMH, or repackage risks differently from other investors.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario